|

|

|

|

Soyuz spacecraft family

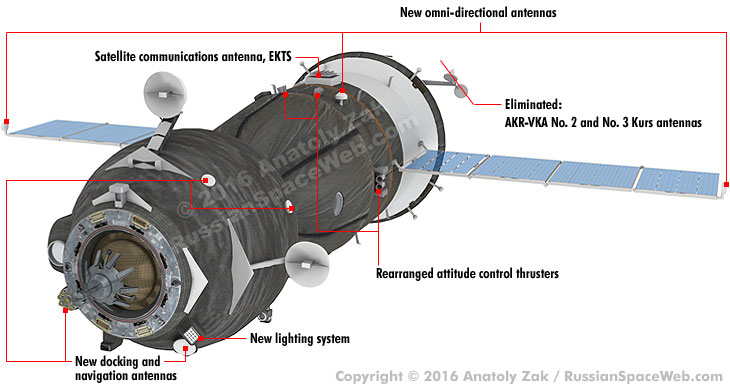

Key new external features of the Soyuz-MS, the latest variant in the spacecraft family. |

||||||||

| SOYUZ DEVELOPMENT HISTORY | |||||||||

|

Origin of the Soyuz spacecraft Conceived in 1960, the Soyuz spacecraft became the second-generation Soviet vehicle capable of carrying humans into space. Unlike its predecessor -- a one-seat Vostok -- the Soyuz would be able to conduct active maneuvering, orbital rendezvous and docking. These capabilities were all necessary for a flight around the Moon and to support lunar landing. In the early scenario of a "circumlunar" mission, defined in 1962, the Soyuz complex would be assembled in the low-Earth orbit out of three consecutively launched elements. |

||||||||

|

Soyuz and Progress anomaly statistics (INSIDER CONTENT) Despite a number of high-profile incidents with Soyuz crew vehicles and Progress cargo ships in the early 2020s, the overall number of problems during their pre-launch testing and flights to the International Space Station, ISS, has been declining steadily, according to internal industry statistics. |

||||||||

SOYUZ

7K-OK VARIANT |

|||||||||

| 7K-OK: Original Soyuz

Compared to its predecessors -- Vostok and Voskhod -- the three-seat Soyuz offered enormous advantages. The most important feature of the new ship would be its rendezvous and docking system. |

|||||||||

|

Despite its roots in the Soviet lunar exploration effort, the first Soyuz spacecraft to reach space was intended for missions in the Earth's orbit. Designated 7K-OK, its main goal was the rehearsal of orbital rendezvous, which would be crucial for a lunar expedition. Missions of Soyuz 7K-OK also had the political goal of shortening the hiatus in the Soviet human space flight program. |

|||||||||

|

On August 28, 1965, the leading designer Aleksei Topol brought Boris Chertok the official schedule for the development of 7K-OK, which had just been approved by Korolev. Chertok could hardly believe his eyes, because by December of the same year, the document required to build and outfit Soyuz prototypes for 13 different tests. |

|||||||||

| In the second half of 1965, after several years on a drawing board, the USSR’s new-generation manned spacecraft started appearing in metal. The final assembly of the Soyuz was centered at Hall 44, led by G.M. Markov, at the Experimental Machine-building Plant, ZEM, in Podlipki, which traditionally served as the manufacturing base for the adjacent OKB-1 design bureau. | |||||||||

| On November 28, 1966, the USSR launched the first test mission of the new-generation Soyuz spacecraft under a cover name of Kosmos-133. The unmanned vehicle was expected to play a role of the "active" ship during rendezvous maneuvers with a "passive" spacecraft scheduled for launch 24 hours later. However things did not go according to plan... | |||||||||

| Hoping to recover quickly from major technical problems in the maiden mission of Soyuz on Nov. 28, 1966, Soviet engineers rushed to prepare the launch of the second spacecraft remaining from the aborted dual flight. With a much better understanding of technical and organizational challenges, leaders of the Soyuz project decided to send the 7K-OK No. 1 vehicle on a solo mission on December 14, 1966. However this time, the launch attempt brought a fatal disaster... | |||||||||

|

The third unmanned test launch of the Soyuz spacecraft aimed to finally deliver a clean performance of the new vehicle and thus open the door for the resumption of the politically important manned space flight in the USSR after a two-year hiatus. The mission lifted off in February 1967 and could be considered a resounding success for the new-generation spacecraft... if not for a nasty surprise at the very end of the flight... |

|||||||||

|

The first manned launch of the Soyuz spacecraft on April 23, 1967, ended catastrophically 24 hours later with the loss of Vladimir Komarov in crash landing due to failure of the main parachute to deploy. |

|||||||||

Joint mission of Soyuz 7K-OK No. 6 and No. 5 (Kosmos-186, -188) In October 1967, a pair of unmanned Soyuz spacecraft, officially identified as Kosmos-186 and Kosmos-188, achieved the world's first fully robotic docking in orbit. This truly remarkable engineering achievement provided a major morale boost for the Soviet space program still reeling from the loss of Vladimir Komarov. |

|||||||||

The Soyuz pair (No. 8 and No. 7) makes flawless automated docking After the problem-ridden first rendezvous in October 1967, Soviet space officials decided to send another unmanned pair of Soyuz spacecraft to dock in orbit. The preparation for the mission was overshadowed by the tragic death in a plane crash of the world's first cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin in March 1968, but, the next month, two Soyuz spacecraft completed the successful automated docking without a hitch. |

|||||||||

Kosmos-238: Last test before return to flight In August 1968, the USSR launched the final dress rehearsal of the newly developed Soyuz spacecraft to re-certify it for piloted flights after the loss of Vladimir Komarov more than a year earlier. Hidden under name Kosmos-238, the 7K-OK No. 9 spacecraft flew the fifth test mission in the wake of the Soyuz-1 accident. |

|||||||||

Soyuz-3: USSR resumes human missions after the accident In October 1968, Soyuz finally returned to flight with a pilot onboard. Right after entering orbit aboard Soyuz-3, a cosmonaut Georgy Beregovoi began manual approach to unpiloted Soyuz-2, but made crucial errors in the darkness of night trying to dock in upside down orientation and severely overusing propellant. |

|||||||||

|

In January 1969, the dual Soyuz mission finally accomplished the rendezvous and the spacewalk of two cosmonauts from one spacecraft to another originally planned for 1966. This experimental flight had long-running implications for future lunar expeditions and orbital assembly. |

|||||||||

| Soyuz-6, -7, -8 spacecraft conduct triple mission

With the Soviet lunar project stalled by the failures of the N1 rocket in 1969, leaders of the rocket industry were forced to invent more spectacular missions based on the available Soyuz 7K-OK spacecraft. The success of the dual piloted Soyuz mission in January 1969, inspired the idea of repeating the docking of two spacecraft, but this time, in view of the third piloted vehicle flying in formation with the first two. The triple mission proceeded from October 11 to October 18, 1969. |

|||||||||

| In June 1970, two Soviet cosmonauts spent 18 days aboard the Soyuz-9 spacecraft, setting a flight-duration record. Theoretically, the mission prepared the Soviet cosmonauts for a possible lunar expedition. However, the price of the achievement was high, providing major lessons for the future. | |||||||||

FOLLOW-ON SOYUZ VARIANTS |

|||||||||

|

7K-L3 (LOK): Soyuz for the Moon In parallel with the development of the 7K vehicle, the Soviet designers worked on a spacecraft designated LOK -- essentially the Soyuz "on steroids," which would be capable of carrying two Soviet cosmonauts into orbit around the Moon. During expeditions on the lunar surface, LOK would play a role of the "mother" spacecraft for the LK lander, which would deliver one crewmember on the surface of the Moon. |

||||||||

|

The Soyuz spacecraft sans Habitation Module was developed for a

circumlunar mission within the L1 project. Officially identified as Zond,

the L1 spacecraft flew several unpiloted test missions with mixed results, until the program was cancelled in the wake of the Apollo success. |

||||||||

|

7K-T: Soyuz for the station With the end of the Moon Race, the USSR quietly shifted its focus in human space flight to the Earth-orbiting station. Accordingly, the Soyuz was re-tailored for the role of a ferry, capable of delivering a crew of three to the outpost. The first such vehicle, designated Soyuz-10, flew in 1971. However the same year, mission of Soyuz-11 ended in a disaster, when its three cosmonauts died as a result of a decompression of their reentry capsule on the way home. |

||||||||

Kosmos-496: Fixing Soyuz-11 flaws On June 26, 1972, the Soviet space program made its first major step on a difficult road to recovery from the Soyuz-11 disaster. The upgraded version of the 7K-T vehicle orbited the Earth without crew in the autonomous flight under name Kosmos-496. |

|||||||||

|

Kosmos-573: Re-confirming Soyuz fixes On June 15, 1973, a heavily modified version of the Soyuz 7K-T spacecraft went into orbit without crew or much publicity on its second mission to confirm that all the lessons from the fatal Soyuz-11 accident in 1971 had been learned. In addition, the test flight sought to resolve problems encounted during the ill-fated launch of a space station a month earlier. |

||||||||

|

Soyuz-12: USSR resumes crew missions after deadly accident On Sept. 27, 1973, the Soyuz-12 spacecraft carried a pair of cosmonauts on a two-day test mission of the new crew vehicle variant modified after the loss of three cosmonauts aboard Soyuz-11 more than two years earlier. |

||||||||

|

Soyuz flies a two-month endurance mission From Nov. 30, 1973, until Jan. 28, 1974, a Soyuz spacecraft without crew secretly orbited the Earth, testing the limits of its onboard systems and setting a new record for its autonomous mission. |

||||||||

|

In December 1973, two cosmonauts launched into space aboard a custom-built Soyuz-13 spacecraft, carrying the Orion-2 telescope for astrophysical observations. During the eight-day flight, the overworked crew collected a wealth of ultraviolet data from mysterious and little-known objects in the Universe. | ||||||||

|

A specialized version of the Soyuz spacecraft originally known as 7K-TM was custom-designed for the joint mission with the US Apollo spacecraft in 1975. It was equipped with a new type of a docking port dubbed APAS for Androgynous Peripheral Attach System. |

||||||||

First rehearsal of a joint mission with Apollo (INSIDER CONTENT) On April 3, 1974, the USSR launched an unpiloted test version of a modified Soyuz vehicle, which it hoped to eventually use for an orbital docking with the American Apollo spacecraft. Despite the international nature of the project, the introduction of the new variant was shrouded in usual Soviet secrecy and was barely documented in history books. |

|||||||||

|

Kosmos-656: First test of a crew transport for Almaz (INSIDER CONTENT) On May 27, 1974, a classified mission, designated Kosmos-656, flight-tested a modified Soyuz spacecraft intended for carrying cosmonauts to the Almaz military orbital lab. |

||||||||

|

Soyuz-14: The USSR launches first military station crew On July 3, 1974, the Soyuz-14 mission carried what was announced as an expedition to the newly launched Salyut-3 space station. In fact, it was a specialized military team heading to the Almaz OPS-2 orbital observation outpost publicly camouflaged behind the civilian space station program. For the first time, a piloted military orbiter armed with a self-defense gun and an array of reconnaissance equipment operated in space. |

||||||||

|

The USSR develops new variant of the Soyuz spacecraft — 7KS Fast-paced upgrades of the Soyuz spacecraft in the early 1970s included work on the most-advanced version of ship at the time, called 7K-S, initially conceived for the military. It never reached operational status but paved the way for the 7K-ST variant (Soyuz-T) which became workhorse of the Russian piloted space program in the 1980s. |

||||||||

|

Kosmos-670: The USSR launches Soyuz 7K-S variant (INSIDER CONTENT) On Aug. 6, 1974, the USSR secretly launched an experimental version of the Soyuz spacecraft that opened a years-long flight test program that would lead to the Soyuz-T variant. The first mission, which lasted two days, was announced under the cover name Kosmos-670, but its true objectives were not acknowledged until the end of the Soviet period. |

||||||||

|

Second rehearsal of a joint mission with Apollo (INSIDER CONTENT) The original test flight program of the Soyuz 7K-TM variant, developed for the Apollo-Soyuz docking mission, envisioned one unpiloted launch and two dress rehearsal missions with cosmonauts onboard. However, numerous technical problems and equipment delays hampering the first test flight in April 1974 prompted Soviet officials to add another pilotless launch in August of the same year. It lifted off without much fanfare under the cover name Kosmos-672 on Aug. 12, 1974. |

||||||||

|

Soyuz-15: The Soviet military crew fails to reach its orbital post On Aug. 26, 1974, the USSR launched the second expedition to the Almaz OPS-2 military space station, operating in Earth's orbit under the cover name Salyut-3. However, commander Gennady Sarafanov and flight engineer Lev Demin failed to dock their Soyuz-15 spacecraft to the outpost, narrowly avoiding a high-speed collision. The crew then urgently headed home after just two days in orbit. |

||||||||

|

Soyuz-16: The USSR launches dress rehearsal for a joint mission with Apollo On Dec. 2, 1974, Soyuz-16 went into orbit with a crew of two to test critical hardware and operations for the upcoming docking with the Apollo spacecraft scheduled in the summer of 1975 |

||||||||

|

Soyuz-17: First expedition to Salyut-4 On Jan. 11, 1975, just three weeks after the launch of the Salyut-4 space station, the USSR orbited its first crew slated to occupy the outpost for nearly a month. During their expedition, members of the Soyuz-17 crew overcome a series of technical challenges to conduct pioneering research in orbit. |

||||||||

|

Cosmonauts escape a close call at launch On April 5, 1975, a Soyuz crew went through a near-death experience when their rocket failed just short of orbital velocity, triggering dangerous fall back to Earth and a risky recovery operation in the mountainous terrain near the hostile border with China. |

||||||||

|

Soyuz-18: Second expedition to Salyut-4 The two-month trip of the Soyuz-18 crew to a space station in 1975, which broke a Soviet flight-duration record, is also widely credited with setting standards and procedures for progressively longer stays of Soviet cosmonauts aboard Earth-orbiting outposts for years to come. |

||||||||

|

In July 1975, the Soyuz-19 spacecraft with two cosmonauts onboard and the US Apollo vehicle with three NASA astronauts conducted a successful rendevous in the orbit around the Earth, becoming a symbol of a short-lived detente period in the Cold War. |

||||||||

|

NEW, Nov. 17: Soyuz-20: Certifying for three-month missions In November 1975, the unpiloted Soyuz-20 spacecraft was launched to the Salyut-4 space station, which itself had no crew onboard at the time. Instead other passengers, such as turtles, were reportedly riding inside Soyuz-20, for a presumed endurance mission, although many of its details remained a mystery for decades. |

||||||||

|

Soyuz T: Transport Inaugurated in 1979, the Soyuz T spacecraft, (T stands for "transport") featured a brand-new motion control system, using a digital computer; a modified propulsion system with an integrated fuel supply system for all engines. Many onboard systems were replaced with newer, better ones. Combined, these modifications allowed to increase the size of the crew back to three, this time pressure suits included. The orbital lifespan of the spacecraft was also increased. In 1980, the Soyuz T carried crew into orbit for the first time. |

||||||||

|

The TM modification of the Soyuz spacecraft, where M stands for "modified," sported the Kurs advanced rendezvous radio system, modified motion control system and radio communication system. It was also equipped with a thruster assembly with segmented propellant and gas stores. The vehicle was launched for the first time unmanned in 1986 toward the Mir space station, and carried its first crew to Mir in 1987. The TM version also became a base for the Progress M series of cargo carriers. |

||||||||

|

In October 1991, during a meeting with Boeing representatives (the main station contractor) the head of NPO Energia Yuri Semenov offered the company's Soyuz spacecraft to serve as a "lifeboat" for Space Station Freedom. On June 18, 1992, NASA Administrator Daniel Goldin and Director General of the Russian Space Agency Yuri Koptev "ratified" a contract between NASA and NPO Energia to study possible use of Soyuz and Russian docking port in the Freedom project. |

||||||||

|

Soyuz TMA: Anthropometric The Soyuz TMA, or "anthropometric" version was designed within US-Russian cooperative program on the International Space Station, ISS. "Anthropometric" upgrades mostly aimed to allow taller crewmembers to fly the Soyuz. The production of the TMA spacecraft, however, was stalled by non-payments by the Russian government to the RKK Energia at the end of the 1990s. Ironically, NASA, which originally ordered the upgrades, at one point, refused to pay for the development of the TMA, until Russia could ensure the future production of the spacecraft. After many delays, the TMA finally flew in 2002. |

||||||||

|

The introduction of the Soyuz TMA-M spacecraft became the latest step in a series of gradual upgrades to Russia's legendary manned transport. Originally designated as Series 700, Soyuz TMA-M was also informally known as "digital Soyuz," -- a reference to an advanced flight control computer onboard. Systems introduced in this round of modifications also promised to pave the way to the development of the new-generation manned vehicle. After some delays, the first Soyuz TMA-M made it to the launch pad in October 2010. In depth: SOTR system (INSIDER CONTENT)|Ventilation system (INSIDER CONTENT) |

||||||||

|

Soyuz MS: The ultimate upgrade?

After nearly half a century of orbital missions, the Russian veteran transport spacecraft got another upgrade in 2016 with the Soyuz-MS variant (also know as Series 730). Soyuz MS replaced Soyuz TMA-M variant. In depth: | Design of Soyuz-MS (INSIDER CONTENT) |Habitation Module, BO (INSIDER CONTENT) | Descent Module (INSIDER CONTENT) | Transfer Section, PKhO (INSIDER CONTENT) | NEW, Dec. 29: Instrument Section, PO (INSIDER CONTENT) | SOTR system | Design of the Soyuz-MS (INSIDER CONTENT) | Kurs-NA rendezvous system | Power supply system | EKTS satellite communications system | Propulsion system | SZI-M "Black box" | Replacing imported avionics on Soyuz MS series (INSIDER CONTENT) | Upgrades to Soyuz-MS and Progress-MS spacecraft (INSIDER CONTENT) |

||||||||

|

The Advanced Crew Transportation System, ACTS, also known as "Euro-Soyuz," emerged during 2006, when Russian company RKK Energia realized that its proposals to replace the Soyuz spacecraft with the Kliper reusable glider would be too ambitious for the current level of funding of the Russian space industry. Instead, a modified Soyuz, with the capability of reaching lunar orbit, would serve as a technological bridge, possibly paving the way to the future development of the Kliper. |

||||||||

|

In the mid-2000s, improving economic outlook for the Russian economy and slowly growing space budget perhaps encouraged RKK Energia to dust off its old plans for building a lunar base. One concept for a lunar transport would include a combination of a Soyuz-derived reentry vehicle with the large habitation section, based on the cabin module of a proposed Kliper reusable orbiter. |

|||||||||

|

NEW, Oct. 8: Soyuz-ROS In 2025, the return to the idea of launching the post-ISS Russian station to the tried-and-tested 51-degree orbit, rather then a hard-to-reach near polar orbit, also renewed interest toward employing the veteran Soyuz spacecraft for transport to the future outpost. |

||||||||

|

USERS' GUIDE TO SOYUZ |

|||||||||

|

Design overview

A classic seven-ton Soyuz vehicle consists of three major components, providing for every stage of flight from orbital insertion to landing. To protect the ship's systems from extreme temperature swings in space, all its surfaces exposed to space, except for active elements of sensors, antennas, windows, the docking hardware, thruster nozzles and radiator panels, are blanketed in multilayer vacuum-screen thermal insulation. |

||||||||

|

Habitation Module

(BO)

The habitation section of the Soyuz spacecraft, carries crucial life-support systems for the crew, including toilet and water supplies. It also provides extra habitation room during the flight and can serve as an airlock for space walks. In most missions, the front end of the habitation section is equipped with docking hardware, allowing the crew to remain |

||||||||

|

Descent Module

(SA)

The reentry capsule of the Soyuz spacecraft, known by its Russian acronym as "SA." is the only section of the vehicle, which returns to Earth at the end of the mission. It contains two or three personally contoured couches where the cosmonauts recline for ascent, descent and landing. Seats are facing controls and displays used for all critical flight activities. |

||||||||

|

Aggregate Compartment

(PAO)

The instrument module of the Soyuz spacecraft, known by its Russian acronym as PAO, or Priborno-Agregatniy Otsek, in its turn is subdivided into three main sections: Intermediate compartment, Instrumentation compartment, PO, and Propulsion compartment, AO. |

||||||||

MISSION PROFILE AND ONBOARD SYSTEMS |

|||||||||

|

From 1971 and well into the 21st century, the Soyuz spacecraft's main role in the Russian space program was to deliver crews to space stations in the low-Earth orbit. The Soyuz could remain in space up to 200 days, when docked to the station and it could orbit the Earth in the autonomous flight for 4.2 days. The autonomous flight would normally be split into two phases: a 2.2-day period spent from launch to docking with the station, and a several-hour long period from undocking to landing with a built-in reserve of two days. |

||||||||

|

For almost half a century, the manned Soyuz spacecraft has ridden into orbit on top of its namesake rocket. Over the decades, the spacecraft and its launch vehicle went through several upgrades, however the launch profile had not changed much. Spent stages of the rocket and other components fall into several designated areas in Kazakhstan and in Russia minutes after their separation. |

||||||||

|

Perhaps the riskiest and scariest part of the Soyuz flight comes at the very end, with the fiery reentry into the atmosphere, followed by a rough touchdown, which, according to many crew members who have experienced it, can only nominally be called soft. |

|||||||||

Integrated Propulsion System (INSIDER CONTENT) The Soyuz is equipped with multiple engines responsible for maneuvers and orientation in orbit. The main engine and two types of multiple attitude-control thrusters are fed from a set of tanks forming a unified system known by the Russian abbreviation KDU. Along with the rest of the Soyuz spacecraft, the KDU went through many re-designs in the course of its decades-long service. |

|||||||||

|

For decades, rockets have remained the fastest and most dangerous mode of transportation created by humans. Not surprisingly, engineers went to great lengths to develop "insurance policies" in case something goes wrong during a wild ride beyond the Earth atmosphere. As it turned out, the most practical way of escaping from a failing rocket would be to use yet another dedicated rocket! Such method was used on American Mercury, Apollo and Russian Soyuz. The latter system had actually got a chance to prove itself in real life emergency situation... |

||||||||

|

The docking was the primary capability of the Soyuz spacecraft during both lunar landing program and numerous space station missions that followed. Several types and reincarnations of the docking hardware were tested between 1967 and 1975, before a long-lived design of the "drog-and-cone system" has emerged. Such mechanism involves a rod on the Soyuz spacecraft, which serves as an active spacecraft during the rendezvous, and a receptive cone, installed onboard the space station. |

||||||||